Volunteer

|

| Stacks of baked bread pudding, awaiting apportioning and distributing |

It is elemental, inevitable, metaphysical, existential, definitive. Everyone who works or volunteers at Food Runners comes face-to-face, nose-to-nose, eye-to-eye and hand-to-hand with the bread pudding: chopping up ingredients, stirring the lava-like mass, scoping it into/onto baking sheets, slicing it, plopping it into cardboard boxes, packing the boxes into cartons and keeping track of the numbers on the whiteboard.

|

| The bread pudding ingredients, awaiting mixing and baking |

It was the morning of my first volunteer shift and the bread pudding had been baked, its metal trays solidly stacked on a a multi-storied cart, each slab cut into twelfths in preparation for dividing. And dispensing.. Bread pudding, savory or sweet, created by the chefs with whatever ingredients are on hand, is a foundation for the Food Runners pyramid of provisions. At least one corner of the prep room at Food Runners is often piled high with bread stuffs of a certain age, past their prime but no less usable (a description that also applies to me, the volunteer). Bagels go into savory pudding; doughnuts into sweet.

|

| Cook gives bagels the bread pudding treatment. |

To call the resulting bread pudding “hearty” is something like referring to King Kong as a monkey. The pudding provides vital nutrition to those who need it, but with some bending of the building codes, it would also be suitable for packing into the foundations of the Millennium Tower, providing fortification that would solve its structural problems.

|

| Out of the oven on its way to be divided |

That first chore was confidence-building. it wasn’t hard to jam slabs of the pudding into rectangular boxes. There was even comic relief, in the last step of the boxing process, when one volunteer or another poured sticky fruit syrup of chocolate sauce over the top of each slice. A tasteful drizzle of this stuff was dispensed through nozzles on top of tall plastic bottles, which make rude-sounding snorts when nearly empty. I giggled like a fourth-grader.

|

| Volunteer Terry Horrigan squirts the sauce onto the bread pudding |

As to the next chore, it took me a few shifts to determine that a push of my gloved paws was key to success at closing the boxes. At some point in the Food Runners experience, every volunteer comes to a crossroads. It is necessary for each to decide whether s/he is an innie or an outie. This has nothing to do with one’s belly button, but is the determining factor of how one closes the small rectangular boxes into which main courses – and bread pudding and bread pudding and bread pudding – are usually packed.

|

| Cook Sandra Zapata on the bread pudding team |

The first few times I was assigned this, I’d glance right and left, studying the methods of the experienced workers. Some slid the tab under the slot, threading it upwards. Others pushed it down through the slot, a method that held best if, upon completing that maneuver, you gave both sides of the flaps a gentle shove. Observation and practice seemed to indicate that I was an innie.

|

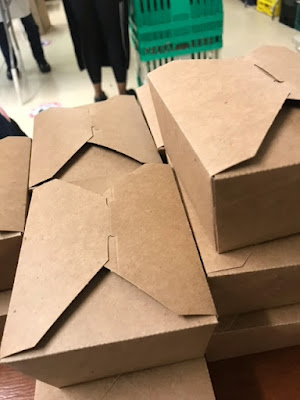

| An example of the "innie" box |

In much the same trial-and-error way, I learned the morning I graduated to taping that it was all in a flick of the wrist. After more than a year volunteering at Food Runners – no big altruism, only one shift a week apportioning food and packing it up, peeling and dicing vegetables – I’d been promoted. At least that’s the way I chose to see the new assignment.

The shift supervisor showed me a tower of banana boxes and handed me a tape dispenser, a wicked-looking tool that was new to me. The banana box, just the right size for packing boxed shipments of food, had a rectangular opening in its bottom. The object, I was shown, is to criss-cross tape at right angles, sticky side up, making it possible to insert a rectangular cardboard patch that fills the hole, thereby creating a suitable carrier for 30 or so individual portions of food. Simple enough.

|

| Banana box tower |

I pulled up my mask, made sure my gloves were clean and started my task, overconfidently, it turned out. My first efforts resulted in macramed tangles of sticky tape that creased and affixed itself to other parts of itself as it lurched off the dispenser, resulting in shameful cellophane clots that rendered it only marginally useful for the job. It was as though the tape was laughing at me.

I was working at a table with other volunteers, and I quickly peeked sideways to see if anyone was looking. They seemed to be concentrating on their own jobs. No one said “ bad job,” or “gee, that’s a lot of tape to be wasting” or even a general “Here, let me show you how to do it.” I’d gotten at least 90 seconds of training, and I was on my own, messing up. It took me 10 minutes, which felt like a humiliating year, until I figured out how to dance to the rhythm of the job – stab, pull, twist wrist to force the misbehaving tape into the maw of the metal teeth that would cut it off – that someone said something: “There you go.”

|

| Chef cooking radishes |

I was particularly clumsy, but the truth was that the job didn’t need finesse; it didn’t need pondering. The goal, from the first day I walked into the facility, was clear, getting food to hungry people. Get masked, get washed, get gloved, get going. There’s no kissing up to a boss, no hiding the knots of wasted tape. Nobody’s polishing apples in hopes of getting a raise. Everybody pulls in the same direction, harnessed to the same plow. There are hungry people, there is excess food. The volunteers and the kitchen staff alike aim to use the latter to eliminate the former. Two thousand meals a day are turned out. It’s that simple.

Fernando Zapata, who is in charge of the kitchen, told me there’s never been need to tell anyone their work isn’t good enough or needs improvement. “Everyone does their best. ... no problems. Everyone is happy, and everyone works hard.”

|

| Volunteer Shonna Enson dishes up servings of pasta chicken |

You’re part of a team at the Food Runners kitchen, and you work after getting a few minutes demonstration from chef Fernando or one of the other cooks, then by watching what the person next to you is doing, or remembering what the person next to you did the last time you worked a shift. After a few sessions, you don’t need anyone to suggest that you could help by spreading the containers out on the table or writing out a bunch of labels for the boxes in which containers of food will be packed.

|

| Volunteer Richard Horrigan collaborates on the pasta chicken |

There is no training manual; there is no employee evaluation, there is no corporate bureaucracy, from the way you sign up to the way you sign in for whatever shift on whatever day you like, to the moment you walk out the door, on a good day with some delicious day-old pastry in hand.

Sometimes we volunteers talk, trading information about kids, jobs, neighborhoods. Sometimes we work silently side by side; that seems as compatible as conversation. Some of the volunteers speak good enough Spanish to chat with the cooks. My Spanish is to their Spanish as, well, my knife skills are to their knife skills.

|

| Cook Santiago Camara tackles a pile of string beans |

Without ever having to talk about a structural chart, it’s clear that the cooks are the ones in charge. We wannabe do-gooders do the kitchen scut-work, as directed by them. It’s a refreshing turnaround from the familiar San Francisco restaurant, where as patrons, many of the volunteers are used to being served by kitchen staff. At Food Runners, we volunteers serve the kitchen staff.

|

| Cook Andres Mena slices potatoes |

The only clash I have ever witnessed or heard is aural. Mexican music is played in the kitchen, and sometimes it is played at the same time that pop music is played in the prep room. Listening to both at once is like trying to dance to two kinds of music at once. two kinds of music at once is like trying to tap dance and do ballet at the same time. I have, on occasion, retreated to a far corner of the prep room (which has its advantage, namely proximity to the snack table).

|

| Cook Edwin Manruque husks ears of corn |

I started volunteering to satisfy an early-pandemic instinct, to find something useful to do while waiting for this horror to go away. I was looking for something in which volunteers’ efforts had a beginning, middle and an end (even if that end i’s as unimpressive as half-filling a plastic tub with peeled potatoes).

|

| Tubs of vegetarian fried rice |

The pandemic grinds on, flowing and waning with each new variant, Food Runners remains constant, a need to be filled, a goal to be met. It’s been an emotional balm.. The volunteers are decent people doing decent work with food that would be otherwise wasted. It’s good for the soul ... and it’s good for the wrists. I am as one with that tape dispenser.