by Suzanne Brais, Volunteer

As five o’clock came around and we unpacked the dinner meal, a delicious chicken in mushroom and onion sauce, potatoes (always a favorite) and salad, I surveyed the scene inside the Przemysl Humanitarian Centre. The Tesco, as the Humanitarian Centre was known, was once a shopping mall on the outskirts of town, anchored by a Tesco grocery store. When the refugee crisis began, it was commissioned by the civic government to house the humanitarian response.

From my vantage point behind the hot food serving counter in the WCK Cafe corner of the Tesco, I looked out over our forecourt of 10 or so tables with cafe chairs and the bubbling scene of families and individuals eating. Behind me, E was working the panini “sweat-box”, as we affectionately called it, toasting paninis just right so that the cheese was melted and the crust crisp. To my right, inside the expanse of what was the Tesco proper, was the sleeping room with thousands of camp beds where everything was swept, cleaned and disinfected daily by an army of young volunteers and, once a week, by the real US army. Straight ahead, beyond the low wooden demarcation of our cafe, down the mall walkway of what once would have been other shops, hung flags from various countries around the world. Under each flag, there was a desk, a person and computer, ready to match refugees with home country welcome programs. The shop spaces had been converted into a first aid station (with crazy amounts of random donated pharmaceuticals), a TV room, a Lego and toy room, a crèche, a counselling room and several rooms of beds specifically allocated to groups of refugees who were about to move as a group to their next country. I waved at Adam - a smiley volunteer from Kansas who staffed the pet-sitter station - he lay half in/half out of a dog cage trying to calm a large hound while its owner showered or ate. That young man was never discouraged, no matter how loud or agitated his charges became. A soccer ball flew through the air above Adam’s station and some young teens careened the tight mall corner on rolling skates. Clearly, the sugar rush of the sweets handed out by the Polish WCK “cookie lady” had kicked in. We still had many hours to go before the end of our 12 hour shift.

At the opposite end of the mall, we could see a line of newly-arrived registering and getting their wrist tags: they were people from all walks of life: farming families, young urban families and their elderly, tech workers, mothers and daughters mainly…warm faces, worn faces, anguished faces, exhausted faces. Entry to the Tesco was tightly controlled. During our time, many of the refugees came from the South and the West, from Malitopul for example. It takes a week so, Sebastian our Polish restauranteur/leader told us, for the waves of refugees to arrive at the Polish border from wherever they may have left their homes and loved ones.

I looked at the individuals sitting in our cafe. They were 24 to 72 hours ahead of the incoming crew in their long journey to somewhere that is not their home. Where should they go? How far away should they go? Should they go with a group or on their own? Should they go by train, bus or car? Some had friends or contacts that they were heading to, most who paused at the Tesco did not. And yet, over their time at the Tesco, most developed a plan.

Most went on to European countries, a few considered North America but most deemed it too far for they hoped to return as soon as possible to their country. The European Union countries were quick to allow any Ukrainian holding a passport with an exit stamp after February 24th to travel for free within the EU and to freely access health care, social care, employment opportunities and education for their children all over the EU.

In the Tesco parking lot, a fleet of brand-new German Audi A5s and even a hockey team touring bus were waiting to carry Ukrainians to their next stops across Europe. Regular shuttles went to the train station. Main urban centres such as Munich and Berlin were already flooded with refugees so countries donated transport to move new groups directly to the smaller town destinations. The Danish government representative would come to us and discuss, over servings of sausage in vegetable sauce, how he was trying to get “his” group out and which ferry they could make to Denmark. He was a super nice guy and, when the time came, a nice group of Ukrainians went with him. Many made a point of coming over to us and giving us hugs and thanks before leaving - tucking a few warm paninis under their arms for the 36 hour bus trip.

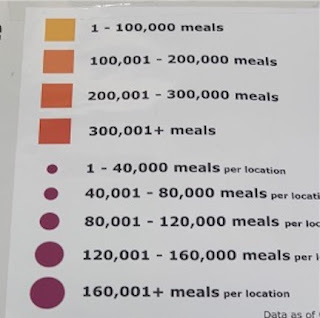

In the kitchen, as rock music blared, the Cold Side mantra was “bun, schmear, salami, peppers, cheese, bun”. Four times a day, trucks full of insulated containers with the freshly produced meals and fresh fruit left the field kitchen and travelled to over 20 sites across Poland, which mainly consisted of the Tesco center, train stations and border crossings. WCK operated similar efforts in Romania, Moldova, Slovakia, Hungary, Germany and Spain but not to the same extent.