by Suzanne Brais, Volunteer

On February 24, 2022, when Putin began his military operation in Ukraine, millions of Ukrainian residents mobilized either to defend their country or to escape the horrors that were to come. Within three days of the first attacks,

World Central Kitchen (WCK) set up operations in Poland and supported the millions of refugees leaving their homes, fleeing the bombing and streaming across the Polish border. Initially, WCK distributed hot soup, tea, coffee and hot chocolate to any and all as soon as they crossed the border. The warm beverages were a welcome relief for the many that had travelled through the cold winter weather.

WCK is dedicated to “immediately serving chef-prepared meals to communities impacted by natural disasters and prolonged humanitarian crises”. As a Food Runner, I had closely followed the work of WCK’s charismatic founder José Andrés since WCK’s ethos is much like that of Food Runners. Like Food Runners, WCK believes in the power of a fresh hot quality meal, well served, to restore and bolster someone’s sense of dignity. Also, like Food Runners, WCK is firmly based in the restaurant sector and works with those who are selling and producing food for the local market. I wanted to see how it worked up close, with a view from the ground and to see if it really was so special. The short answer is: yes!

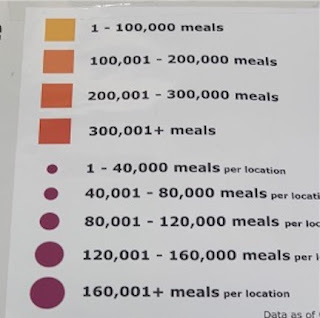

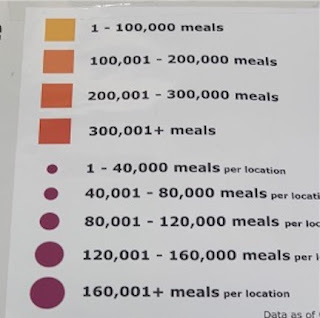

The picture above shows the scale and coverage of the WCK operation outside of the Ukraine as of the beginning of May 2022. Within the Ukraine, WCK has worked tirelessly through local restaurants and chefs to provide free meals to the internally displaced and also to deliver bags of groceries to those residents caught on the front lines.

WCK’s work in Poland was centered out of Przemysl. The closest large town to the border, Przemysl has a main train station and numerous highways radiating across Europe. This became a main staging post for refugees to rest, recoup and plan their onward travel. Two weeks after the war began, WCK set up a relief kitchen in Przemysl with 12 massive paella pans, 12 ovens and eventually a large walk-in fridge. The idea was to use local food production channels to greet the refugees who had left the comforts of their home and could no longer access hot, nutritious meals. Chefs from Poland and around the world responded. Over the next 5 months, 1,500 volunteers along with 112 local partners served over 11.5 million meals to people in Poland alone. My Chef friend E and I were just two of that team.

E and I found two placements in “distribution” on the WCK’s efficient online sign-up site for a month’s time and set about booking flights. Through E’s chefs’ network, we reached out to @chefmarcmurphy who was already in Przemysl and apparently working in the WCK kitchen. He is a man of few words. He texted us the name and number of a contact who could help with accommodation and answered our multitude of questions of what to bring with simply: “Bring apron."

The Tesco Center

Once in Przemysl, E and I were assigned to two placements: one in the recommissioned Tesco shopping centre on the outskirts of town and the other in the WCK field kitchen closer to the train station. No photographs were allowed in the Tesco, so here is my best effort to relay the scene:

As five o’clock came around and we unpacked the dinner meal, a delicious chicken in mushroom and onion sauce, potatoes (always a favorite) and salad, I surveyed the scene inside the Przemysl Humanitarian Centre. The Tesco, as the Humanitarian Centre was known, was once a shopping mall on the outskirts of town, anchored by a Tesco grocery store. When the refugee crisis began, it was commissioned by the civic government to house the humanitarian response.

From my vantage point behind the hot food serving counter in the WCK Cafe corner of the Tesco, I looked out over our forecourt of 10 or so tables with cafe chairs and the bubbling scene of families and individuals eating. Behind me, E was working the panini “sweat-box”, as we affectionately called it, toasting paninis just right so that the cheese was melted and the crust crisp. To my right, inside the expanse of what was the Tesco proper, was the sleeping room with thousands of camp beds where everything was swept, cleaned and disinfected daily by an army of young volunteers and, once a week, by the real US army. Straight ahead, beyond the low wooden demarcation of our cafe, down the mall walkway of what once would have been other shops, hung flags from various countries around the world. Under each flag, there was a desk, a person and computer, ready to match refugees with home country welcome programs. The shop spaces had been converted into a first aid station (with crazy amounts of random donated pharmaceuticals), a TV room, a Lego and toy room, a crèche, a counselling room and several rooms of beds specifically allocated to groups of refugees who were about to move as a group to their next country. I waved at Adam - a smiley volunteer from Kansas who staffed the pet-sitter station - he lay half in/half out of a dog cage trying to calm a large hound while its owner showered or ate. That young man was never discouraged, no matter how loud or agitated his charges became. A soccer ball flew through the air above Adam’s station and some young teens careened the tight mall corner on rolling skates. Clearly, the sugar rush of the sweets handed out by the Polish WCK “cookie lady” had kicked in. We still had many hours to go before the end of our 12 hour shift.

At the opposite end of the mall, we could see a line of newly-arrived registering and getting their wrist tags: they were people from all walks of life: farming families, young urban families and their elderly, tech workers, mothers and daughters mainly…warm faces, worn faces, anguished faces, exhausted faces. Entry to the Tesco was tightly controlled. During our time, many of the refugees came from the South and the West, from Malitopul for example. It takes a week so, Sebastian our Polish restauranteur/leader told us, for the waves of refugees to arrive at the Polish border from wherever they may have left their homes and loved ones.

I looked at the individuals sitting in our cafe. They were 24 to 72 hours ahead of the incoming crew in their long journey to somewhere that is not their home. Where should they go? How far away should they go? Should they go with a group or on their own? Should they go by train, bus or car? Some had friends or contacts that they were heading to, most who paused at the Tesco did not. And yet, over their time at the Tesco, most developed a plan.

Most went on to European countries, a few considered North America but most deemed it too far for they hoped to return as soon as possible to their country. The European Union countries were quick to allow any Ukrainian holding a passport with an exit stamp after February 24th to travel for free within the EU and to freely access health care, social care, employment opportunities and education for their children all over the EU.

In the Tesco parking lot, a fleet of brand-new German Audi A5s and even a hockey team touring bus were waiting to carry Ukrainians to their next stops across Europe. Regular shuttles went to the train station. Main urban centres such as Munich and Berlin were already flooded with refugees so countries donated transport to move new groups directly to the smaller town destinations. The Danish government representative would come to us and discuss, over servings of sausage in vegetable sauce, how he was trying to get “his” group out and which ferry they could make to Denmark. He was a super nice guy and, when the time came, a nice group of Ukrainians went with him. Many made a point of coming over to us and giving us hugs and thanks before leaving - tucking a few warm paninis under their arms for the 36 hour bus trip.

The Polish operation of WCK was unlike any other in its use of volunteers. In the field kitchen, there were perhaps 15 chefs on the Hot Side (read paella pans and ovens), cooking daily soups, meals and baked goods and about 30 chefs and ordinary folk like us on the Cold Side mainly tasked with assembling thousands of calorie rich paninis with delicious meat and vegetarian options each day. In our time in the kitchen, the professional side was run by a quiet Frenchman rumoured to have worked at a famous 5 star restaurant in Northern Spain. The talent coordinator, who lined up the senior chefs into the future, was the manager from Single Thread.

In the kitchen, as rock music blared, the Cold Side mantra was “bun, schmear, salami, peppers, cheese, bun”. Four times a day, trucks full of insulated containers with the freshly produced meals and fresh fruit left the field kitchen and travelled to over 20 sites across Poland, which mainly consisted of the Tesco center, train stations and border crossings. WCK operated similar efforts in Romania, Moldova, Slovakia, Hungary, Germany and Spain but not to the same extent.

The lunch and dinner menus included: chicken in vegetable sauce, rice and steamed vegetables, sausages in a tomato onion sauce with potatoes and salad, pasta with mushroom sauce and vegetables. There was always lots of bread, a fresh soup, fresh fruit and freshly baked cakes.

The food order and necessary quantities were updated frequently. A breakfast oatmeal, which was perfectly spiced (a recipe one of the Chefs brought from the Four Seasons in Philadelphia), was a big hit with the volunteers but was not a favourite with Ukrainians. It was subsequently discontinued. When we asked for more fresh vegetables, such as the delicious cucumber and sour cream and dill salad that had been consumed very quickly, the Chef laughed: “there were more 5-star Chefs in the kitchen chopping cucumbers as fast as they could than I have ever seen.”

World Central Kitchen Background

World Central Kitchen grew out of DC Central Kitchen, an organization founded in Washington DC, by Robert Egger in 1989. Instead of simply picking up wasting food and turning it into balanced meals for the homeless shelters in DC, it used that process to help unemployed Washingtonians trade homelessness and addiction for real careers in the culinary industry. It has delivered dignified meals to the city’s homeless shelters for over 30 years on contract.

Spaniard chef José Andrés first walked into DC central kitchen in 1994: “ A young immigrant cook searching for my place in the new city and the world” he says. Years later, as Owner of ThinkFoodGroup, the charismatic Chef was also Chair of DC Central Kitchen. When an earthquake devastated Haiti in 2010, Andrés went to cook alongside displaced Haitians in a camp and found himself learning how to cook food the way locals like it. He calls food “a plate of hope”. Since then, disaster after fire, WCK has orchestrated food support. The Ukrainian operation is its first war response and it has been huge in scale. The Polish operation has now closed as the stream of refugees out of Ukraine has lessened but the focus is very much on working within Ukraine with Ukrainians.

Recently, Jeff Bezos has donated a $100 million “Courage and Civility prize” to José Andrés who in turn gave it to WCK. This has boosted their operations. The organization is now active in responding to the fires in California, the floods in Kentucky and events in such areas as Pakistan, Puerto Rico and the Mexican border. In his acceptance speech, Andrés said ”World Central Kitchen was born from the simple idea that food has the power to create a better world. A plate of food is a plate of hope…it’s the fastest way to rebuild lives and communities….people don’t want our pity, they want our respect…the least we can do is be next to them when things are tough…”

This last line in particular echoed something that an elderly man had said to E and me as we were leaving the Tesco centre one evening. We were by the outside cafe area saying goodbye to our Tesco colleagues, I asked E if she felt it made any difference that we were in Poland as compared to WCK employing more Polish personnel. An elderly gentleman looked directly at me and said quite clearly in his best English: “It is very important you (pointing at E and me) are here.” I guess his answer echoed Andrés’ line that we were there to “respect, witness and being next to people when times are tough”. I would argue that Food Runners plays this same crucial role in San Francisco as it delivers “a plate of hope” to those it serves daily across the city.

The End.